Consuelo Vanderbilt, the Duchess of Marlborough: A Real Downton Heiress

In 1895, Consuelo Vanderbilt, 18-year old sister of William K. Vanderbilt, Jr, was "encouraged" by her mother Alva to marry Englands's Duke of Marlborough. In a 2010 post in MailOnline, author Tony Rennell suggested Consuelo was one of the real American "Downton heiresses" who married into and saved the British aristocracy.

Enjoy,

Howard Kroplick

MailOnline

Like Cora in TV's Downton Abbey, scores of American heiresses came to Britain at the turn of the century in search of a hard-up toff to marry. And they may very well have saved our aristocracy...

By Tony Rennell

Updated: 16:30 EST, 22 October 2010

The transatlantic broker made no bones about his blue-blooded trade in envy, ambition, greed and snobbery. He was on the lookout, his advertisement stated, for 'dukes, marquesses, earls or other noblemen desirous of meeting young, beautiful and rich American heiresses for the purpose of marriage'.

In stately homes the length and breadth of England, affronted aristocrats haughtily raised their eyebrows - the impertinence, dammit! Then they shuddered at the soaring cost of running their grand houses and extensive estates and their increasing need to sell off acres and heirlooms to finance their privileged way of life.

With bankruptcy beckoning, they suddenly saw some merit in the business he was touting. Cash for kudos - an injection of much-needed capital from the land of plenty in return for a pukka pedigree.

Perhaps it was just such a marriage broker who in the 1880s eased the passage of the fictional, cash-strapped Earl of Grantham into the arms of the delightful Cora, his super-rich American-born wife, in ITV's hugely popular upstairs-downstairs drama, Downton Abbey.

Keeping the magnificent house he loves - 'where I was born and hope to die... it is my life's work' - comes at a cost that can only be met by dollars. To save his way of life, he becomes a self-confessed fortune-hunter. With Cora's wealth blended to his breeding, Downton lives on.

And so did scores of real-life Downtons dotted around the country. From late-Victorian times onwards, such transatlantic transactions became commonplace as hundreds of socially ambitious 'dollar princesses' like Cora - drawn from the US's 4,000 millionaire families - bought themselves prime positions in the upper echelons of the British aristocracy.

One of the first was Winston Churchill's mother, Jennie. Daughter of a hugely rich Wall Street speculator, Leonard Jerome, she married Lord Randolph, the Duke of Marlborough's younger son, in 1874.

Though the union turned out to be a genuine love-match, it was very nearly scuppered at the start when the families disagreed on the prenup 'terms'. Finance outranked romance. Only after some hard bargaining over who got the dowry in the event of Jennie's death did the couple reach the altar.

But the Jeromes were B-list millionaires compared with the unspeakably rich Vanderbilts. A generation later, the 18-year-old Consuelo Vanderbilt hooked and reeled in the Duke of Marlborough himself. (Or was it the other way round - who was the fisher and who the catch? That was always the question.)

The wedding was a frenzy of opulence. Rubbernecking New Yorkers, awed by this unprecedented combination of cash and class, queued halfway down Fifth Avenue just to view the presents.

By now, prenup negotiations were as hard-fought as a dynastic royal marriage in the Middle Ages or a Wall Street takeover bid.

In the end, Consuelo got the title and the social standing her pushy and unpleasant mother craved, the Duke a dowry of £2million ( equivalent to around £80 million today) to top up the ancestral coffers.

But that was just for starters. In the coming years, the Vanderbilts shelled out as much as £10 million towards keeping the Marlboroughs in the ducal style they were accustomed to. The marriage saved them from going under.

The go-between for this particular deal was Minnie Paget, a New York heiress herself (though several leagues below the Vanderbilts). In London, she grabbed the grandson of a marquess for herself, bringing a modest dowry of £65,000 to the match but then showing her true worth by setting up as a society hostess of considerable distinction and connections.

Hobnobbing with the Prince of Wales's set, she was well-placed to steer fellow Americans such as Consuelo towards any coronet that was going spare. Not that American mothers with social ambitions for their heiress daughters were short on information about 'prospects'.

There was Burke's Peerage to thumb through, of course. But New York also had a society magazine, The Titled American, which not only profiled those women who had already made it into the aristocracy but also carried details - updated quarterly - of eligible noblemen currently on the market.

Title, ancestry, age, family seat and acres were laid out, along with income (or lack of it). The information that the Marquess of Winchester was 'the Hereditary Bearer of the Cap of Maintenance' - part of the royal regalia - must surely have puzzled but also thrilled Park Avenue matrons as they pored over its pages in search of the right son-in-law.

Some girls and their mothers found the prestige they were looking for in the extensive royal families of Italy, Austria, Russia and France. The heiress to the Singer sewing machine fortune was transformed into the Princesse de Polignac on marriage to her French prince.

But, exotic as life might be in Paris or St Petersburg (or Monaco, where Alice Heine of New York married Prince Albert, 67 years before Grace Kelly bagged Rainier), it was London and the English aristocracy that drew most American girls with an eye for a title.

In 1895, the year of the Vanderbilt-Marlborough nuptials, no fewer than nine US heiresses married into titles. One of these, Mary Leiter, daughter of a wealthy department store owner from Chicago, brought a dowry of £650,000 (plus a grand house on Carlton House Terrace) to finance the political ambitions of her husband, George Curzon. She managed the greatest social leap of any dollar princess of her day by ending up shortly after as Vicereine of India, alongside her husband, the Viceroy.

On the other hand, Cora Colegate, widow of a soap tycoon, married the Marquess of Strafford, ploughed hundreds of thousands of dollars into his family home, then lost it all - much her like her namesake Cora in Downton looks set to do - when he died and the estate went to his nephew.

The flow of eligible young women from America was eventually so extensive that author Frances Hodgson Burnett coined a word for it - the 'shuttle'. But, once here and embedded in a blue-blooded family, how did they fare?

Some loved the status - the Duchess of Roxburghe (née May Goelet, daughter of a property tycoon) was in raptures at being welcomed to her new home, Floors Castle, by 100 torch-bearing tenants and a pipe band. Many others, however, hated the arctic cold of stately piles in winter and the suffocating routines of aristocratic living.

A number of marriages ended in the disaster of divorce. Cue even more bitter wrangling over money.

More to the point, however, was the question of how British society took to them. Bertie, the Prince of Wales and later Edward VII, adored these American parvenus for being 'livelier, better-educated and less hampered by etiquette'. His lead helped their acceptance by the snobs.

But the free-and-easy ways he so admired were scorned by others. There were still plenty of high-society snipers for whom 'yank' and 'vulgarity' would always be the same thing. No breeding. No background. No manners. They gushed. They flaunted their furs and their diamonds. They said what they thought. They demanded hot showers and central heating.

Those who managed to contain their New World ways were highly praised. Tatler's accolade went to the Marchioness of Ormonde, who, though she hailed from New York, 'is often mistaken for English-born'.

Not even Downton's Cora is awarded such praise, for all her sweet nature, sense and sensibility. She dares to ask about the credentials of a possible suitor for her daughter's hand: 'Is the family an old one?' A swift put-down comes from her dragon of a mother-in-law, the Dowager, still put out after a quarter of a century at having to have an American bride in the family. ' Older than yours, I imagine,' she snaps.

Even Cora's own flesh and blood are strangers. When stuck-up daughter Lady Mary expresses her disgust at the thought of marrying a middle-class man 'who can barely hold his knife like a gentleman', Cora is shocked at such class-driven arrogance and pomposity.

'Oh you wouldn't understand,' Lady M flounces back. 'You're American...'

Yet the special relationship with America's heiresses flourished, and in the 30 years before World War I, the equivalent of £15 billion in today's money came shuttling across the Atlantic to prop up Britain's tottering aristocrats and their stately homes.

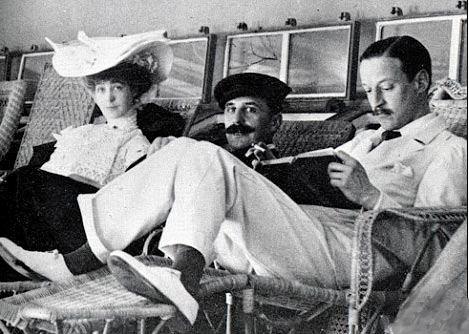

The Duchess of Marlborough at the 1905 Vanderbilt Cup Race

The Duchess of Marlborough had a front row grandstand seat for the 1905 Vanderbilt Cup Race. She obviously attracted the 1905 papararzzi.

Consuelo's mother, Alva Vanderbilt, can be seen standing at the far left.

More Information on Consuelo Vanderbilt:

Comments