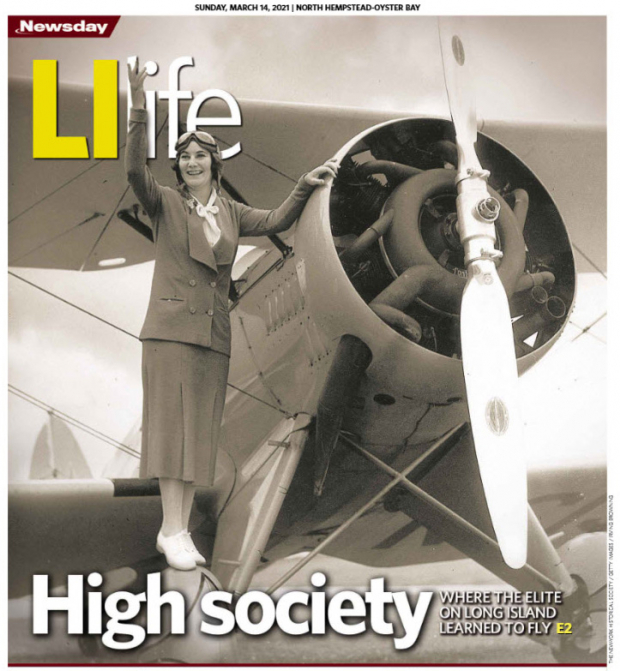

Newsday LI Life: High Society -Where the elite on Long Island learned to fly

In a Newsday LI Life cover article, Lawrence Striegel last Sunday reported on the history of the Long Island Aviation Club for the article, Striegel interviewed Josh Stoff, Richard Sloan and me. VanderbiltCupRaces.com and the Motor Parkway even got shout-outs!

Enjoy,

Howard Kroplick

High society- Where the elite on Long Island learned to fly

Flying First Class

How swells celebrated at LI Aviation Country Club

By Lawrence Striegel

Special to Newsday Updated March 15, 2021 2:52 PM

Whirling propellers chopped the sky as a droning procession of dozens of planes carrying business magnates, aviation mavericks and government officials landed on a grass field south of downtown Hicksville. With the new Goodyear blimp Mayflower bobbing nearby, death-defying stunt flyers, military biplanes in formation and a parachutist entertained some 500 people below.

It was June 29, 1929, dedication day of the Long Island Aviation Country Club, then a new concept in active leisure for the ultrarich but now a little-known slice of local history.

At the time, Herbert Hoover was a new president, master builder Robert Moses would unveil his Jones Beach masterpiece just five weeks later, and a great stock market crash loomed a few months away.

The festivities at this genteel brand of airport and the era’s infectious fever to fly higher, faster and farther were fueled in part by Charles Lindbergh’s heroic solo flight to Paris just two years earlier — an adventure launched at nearby Roosevelt Field.

Lindbergh himself was the most famous member of this country club — a sort of next-generation cross between traditional golf and yacht clubs — where aviation’s elite mixed with "a group of amateur flyers with well wadded wallets," as Newsday once described it.

"If Gatsby owned an airplane, he would have kept it at the country club," said Joshua Stoff, curator of the Cradle of Aviation Museum in Garden City.

Members bore gilded names including du Pont, Morgan, Gardiner, Rockefeller, Guggenheim and Whitney. Member William K. Vanderbilt II’s famous Long Island Motor Parkway ran along the airfield's southern border. The club's aviation luminaries included Amelia Earhart, an honorary member; engine inventor Charles Lawrance, its president; pioneering flyer Jacqueline Cochran; and leading aircraft builders Leroy Grumman, Sherman Fairchild, Walter Beech and Grover Loening. Jazz band leader Roger Wolfe Kahn — son of banker Otto Kahn, the builder of Huntington's Oheka Castle — was a member of the club's flying committee.

'Very exclusive'

The Hicksville chapter set the standard for a national plan to build 114 aviation country clubs "so anyone who was a member and flying cross country could stop at another one and eat dinner there, hang out by the pool, rent a room, whatever," Stoff said. "Obviously, it was only for very wealthy people, very exclusive."

By 1929, flying machines were common in the skies over then-rural and mostly flat Long Island, and airfields multiplied. In Nassau County, Roosevelt Field, Curtiss Airfield and Mitchel Field were back to back to back. "But the Long Island Aviation Country Club was unique," Stoff said.

The contrast with ordinary airports was evident on that windy opening day. Women dressed in flowery chiffons and bell-shaped cloche hats, and men wore suits, knickers and dark jackets and khakis to enjoy lunch under a striped tent, hear official speeches and watch aerobatics by legendary Army flyer Jimmy Doolittle. "Several girl aviators wore stunning gabardine costumes of white or tan, one piece, belted and helmeted models which were very flattering to their tall, slim figures," reported Sunrise, a Long Island magazine.

Life magazine called the club "the swankiest of its kind in the country." Wealthy members drove down from their Gold Coast estates for flying lessons, tea by the pool, sets of tennis and roller-skating parties of 250 people in the emptied-out hangar. The Colonial clubhouse provided an observation lounge with wide windows, a bar, a restaurant and rooms to stay overnight. Full-time mechanics in clean white jumpsuits stood by to hand-start a propeller or fix a balky engine.

Airplanes were the new status symbol, and as one magazine said, " … the pilot's helmet is the swank thing, le chapeau pour le sport." Sportsman Pilot magazine advertised "air yachts" that could whisk New York business owners off to weekend retreats in Canada or let a foursome shun "rail and road crowds" en route to the Harvard-Yale football game.

Ships ranged from biplanes with open cockpits to steel-hulled multipassenger aircraft with closed cabins. Lawrance, the club president, wrote in 1930 that 50 planes were privately owned, and the club owned four more for use by more than 180 members.

An 'exacting instructor'

Just a month before opening day, Lindbergh had married Anne Morrow, daughter of a U.S. diplomat. Later, Lindbergh bought her a Brunner-Winkle Bird biplane and taught her to fly at the club. In her 1973 book "Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead," Anne Morrow Lindbergh described herself as "challenged, frightened, and infuriated" after hours of "trying to satisfy my exacting instructor."

"I myself was infinitely relieved, each time I hit the earth, no matter how hard, to get down alive," she wrote, adding that Lindbergh repeatedly insisted that she try again. She eventually made her first solo from the country club, flying over New York City's towers to Teterboro Airport in New Jersey — "my dream as a young girl at last come true."

In 1932, the Lindberghs endured the kidnapping and killing of their 20-month-old son, Charles Jr. Amid a suspect's sensational murder trial and execution, the Lindberghs retreated to Europe, but they returned in 1939. Staying on Lloyd Neck, the family would visit the country club in Hicksville.

In "The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh," the pilot tells how in August 1940, he took son Jon flying and let the 8-year-old briefly take control. At 6,000 feet, Lindbergh delighted his son by performing "wing overs and two loose loops."

A few weeks later, again with Jon, Lindbergh practiced takeoffs and landings at the club. "I have done very little flying this summer and am anxious to keep in practice," he wrote. (Lindbergh led calls for U.S. isolationism, but after the United States entered World War II, he flew in combat against Japan.)

Through the 1930s, even in the depths of the Great Depression, society-page items told of fun at the Aviation Country Club, especially summer seaplane trips during which men sported black-and-white captain's hats with the ACC logo.

In 1931, a party of 50 people in 11 planes left the Seawanhaka Yacht Club near Oyster Bay "with golf clubs, tennis rackets, dancing pumps, wives and friends," the New York Herald Tribune said. The party "circled the Brooklyn end of Long Island, dropped down for lunch and a round of golf along Great South Bay," and then flew to stay overnight at Watch Hill, on the southern tip of Rhode Island.

Bud and Betty Gillies, a young couple who were both pilots and who would become prominent in aviation, enjoyed the trips. In 1933, Betty, then 25, wrote about the country club’s seaplane outing upstate to Lake Champlain. She and Bud flew in a twin-engine amphibious plane as guests of Powel Crosley, a major maker of radios and the future owner of the Cincinnati Reds.

"Well, we got off for Westport [New York] about 10:30 a.m. Ten ships, from Sands Point," Betty wrote in a diary entry shared by her granddaughter, Glen Gillies, of Rancho Santa Fe, California. " … Never have I enjoyed a ride more! 2 hrs. 5 min. to Westport. Cocktails greeted us on our arrival, and the party wasted no time getting under way. We spent the afternoon at the Yacht Club, swimming and sunning with a most congenial crowd. A big dinner party at the Inn, and a dance at the golf club which lasted until dawn. We broke away about 3:30."

Wowing spectators

One observer of the club was a Hicksville girl named Beth Benoit, now Beth Baranello, 87, of Lake Charles, Louisiana. Her family lived on Alexander Avenue, north of the airfield, just a potato field away. Sitting on a swing, she would smile and wave back at flyers overhead in open cockpits. However, her father, fuel truck driver Charles Benoit, hated that pilots in their noisy planes used the family's roof to line up their landings on the grassy field, which had no runways.

"They would aim at that and then just come right in and land nicely — and it drove my father crazy," she said recently by telephone. "If it was a weekend and they were busy, he would go out and throw rocks at them."

The club would call her dad to complain, Baranello said. "He would say, 'Well, if I could hit them, then they’re too damn close!'"

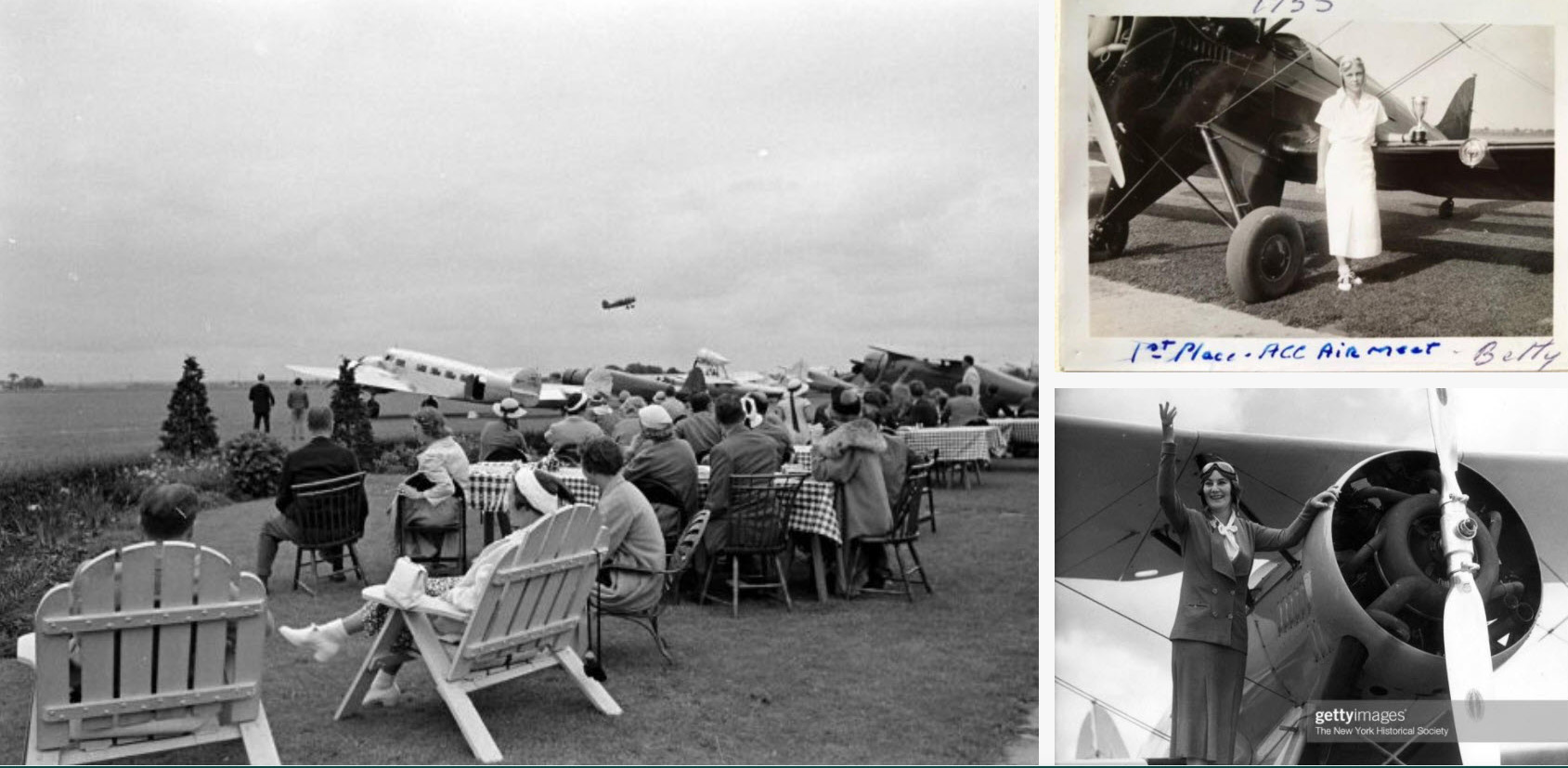

Young Ruth was among the local residents who gathered at the airfield's perimeter each June to watch major air meets with competitions and demonstrations of the newest military and civilian aircraft. They saw balloon-bursting events, simulated dogfights, dives from miles high and one-wheel landings. In 1935, club official Luis de Florez, a respected aviation engineer, won a bomb-dropping competition by releasing a weighted bag from 500 feet to within a foot of a bull's-eye on the field.

At that meet, Betty Gillies won a round-trip race between Hicksville and Connecticut, before which flyers had to predict their times.

"First event was a precision cruising race to New Haven and return, which I won (being only 10 seconds late)," she wrote in her diary. "Luiz DeFlorez [sic] had put up a trophy for it, so I was delighted! I didn't enter any other contests, so spent the afternoon relaxed. It blew a gale all day."

In 1940, TWA gave rides to club family members on a DC-3 airliner labeled "The Lindbergh Line." Among children there was Jan Reddig, the 5-year-old daughter of club member James Reddig, the chief assistant engineer to Grover Loening. Alan Reddig of upstate Webster, Jan’s younger brother, said his sister, clutching a baby doll, was delighted to receive a stick of gum from a flight attendant after her ride. (In the late 1980s, Jan Coggeshall would become mayor of Galveston, Texas.)

The festive tone of the club's first decade wouldn't last. After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, private flying was restricted for security concerns. Betty Gillies then flew for the Civil Air Patrol out of the club and soon became the first pilot to qualify for the Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (later joined into the Women Airforce Service Pilots, or WASPs). Her husband, Brewster Allison "Bud" Gillies, who had tested and sold planes at the club, became a vice president of Long Island’s Grumman Corp., among the nation's biggest builders of warplanes.

After the war, the country club resumed activities, but eventually succumbed to other forces. It had fewer members, and demand for housing for young veterans was high. "You know, suburbia USA," said Stoff, the museum curator, "that’s when a lot of these smaller airfields all disappeared."

In March 1950, as mass-produced homes closed in, the country club was sold to Levitt & Sons for $175,000. Newsday reported that planes flew there until the end, with a gala set for April 1.

"It's all over but the laughing and crying," the report said, "and members will do both on Saturday night when they hold their last whirl in the old clubhouse."

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

On the trail of history

Richard Sloan is passionate about the Long Island Aviation Country Club.

Sloan, 77, a retired TV audio engineer from Massapequa, has long been fascinated by aviator Charles Lindbergh. So when he found out about a unique local airfield where Lindbergh flew, he dug into the history of the Long Island Aviation Country Club. The exclusive club operated from 1929 to 1950 on 80 to 100 acres (accounts differ) south of downtown Hicksville before being sold for construction of Levittown homes. Today, the site is roughly surrounded by Blacksmith Road.

"A marker should be erected to point out that an airport with such a colorful history once existed there," he said recently.

In 2016, Sloan presented a detailed history of the club to the Town of Hempstead Landmarks Commission. On Oct. 24, 2017, the panel approved language for a historical marker. Commission member Joshua Soren said in January that the marker can probably be placed “within the next year.”

Evidence that the aviation club existed at the site is scarce. Sloan said one reminder is Pilot Lane, a short street between Blacksmith Road and Jerusalem Avenue.

But there are other clues.

After the airfield was sold in 1950, historians say, pieces of the club's Colonial clubhouse were moved to create homes on Cliff Drive and Plainview Road. In particular, history buffs say two large pieces of the clubhouse were attached to create a single-family home on Field Avenue in Hicksville. Thomas Losco has lived there since 1975. He said he had heard his home might once have been a barracks, but he didn’t know more until contacted for this story.

Howard Kroplick, a former North Hempstead Town historian, has posted an analysis of Losco's home, with maps, diagrams and photos, at vanderbiltcupraces.com, his extensive website about the Long Island Motor Parkway.

In addition, Kroplick said he thinks one of the country club's two curved hangar roofs was salvaged and now covers a commercial building at Revere and Lexington avenues in Bethpage.

Another trace of the club is a colorful mural above the auditorium entrance at Hicksville Middle School. Painted during the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s, it depicts planes flying above long luxury cars.

— Lawrence Striegel

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Clockwise from above: Long Island Aviation Country Club was photographed in 1937 by Life magazine's Alfred Eisenstaedt. (Photo by The Life Picture Collection via Getty Images / Alfred Eisenstaedt) An aerial view of the country club, 1938-1940. (Hans Groenhoff Photographic Collection, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum) This image of the club's pool and other amenities is framed on a wall in the archives of the Cradle of Aviation Museum in Garden City. (Photo by Cradle of Aviation Museum)

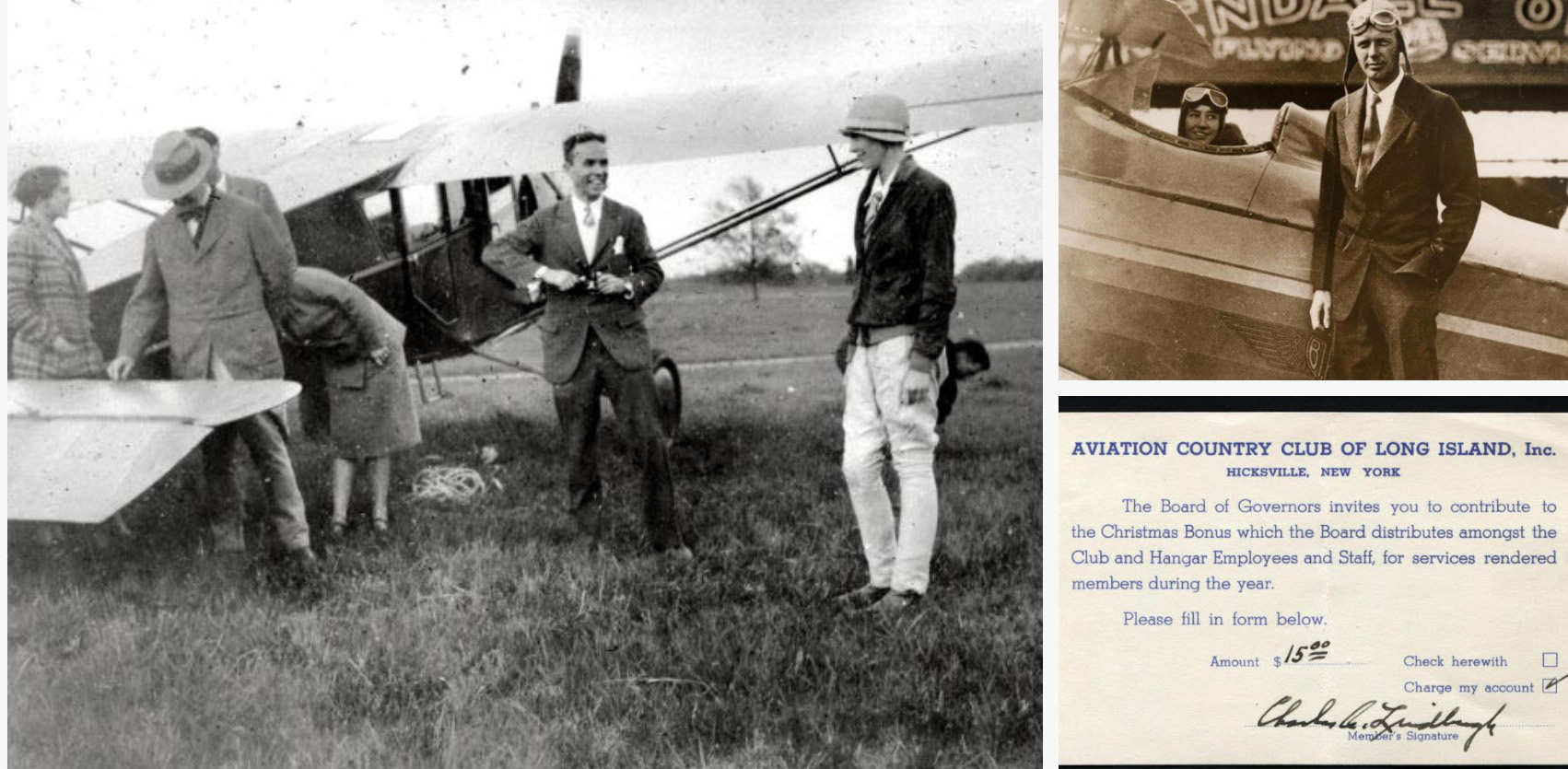

Clockwise from above: Grover Loening, second from right, an American aircraft manufacturer, and Amelia Earhart, right, at the Long Island Aviation Country Club, unique among the Island's airfields. (Photo by Alamy) Anne Morrow Lindbergh learned to fly in the Bird biplane with her husband, Charles A. Lindbergh, as her instructor at the country club. (Lindbergh Picture Collection) Charles Lindbergh's signed Christmas bonus card for the country club staff. (Photo by Alan Reddig)

Clockwise from above: The aviation country club's members, who bore gilded names including du Pont, Morgan, Gardiner, Rockefeller, Guggenheim and Whitney, are seen in this 1937 photo. (Photo by The Life Picture Collection via Getty Images / Alfred Eisenstaedt) Aviator Betty Gillies, in a photo shared by her granddaughter, with a trophy after a 1935 air meet at the country club in which she took first place. (Photo by Gillies Family) Stage and screen actress Juliette Day poses on a Waco biplane at the country club in 1930. She and her husband, Paul Whitney, lived at Whitday Farm in Fort Salonga. (Photo by Getty Images / The New-York Historical Society / Irving Browning)

Clockwise from above: A TWA DC-3 draws a crowd on family day at the country club on June 30, 1940. On family day, members and their children were given plane rides. (Photo by James Reddig) Held aloft by her uncle William E. Reddig, Jan Reddig, whose father was a club member, is delighted with a stick of gum that flight attendants gave out after planes rides on that day in June 1940. (Photo by James Reddig) A locator map from the club's 1940 membership book. (Howard Kroplick)

Clockwise from above: Richard Sloan at Pilot Lane and Blacksmith Road in Levittown where the country club once stood. (Newsday Photo / Steve Pfost) Joshua Stoff, curator of the Cradle of Aviation Museum in Garden City, holds a piece of monogrammed dinnerware from the Long Island Aviation Country Club. (Photo by Chris Ware) A Works Progress Administration mural at Hicksville Middle School memorializes the aviation country club. (Hicksville School District)

The online version of the article also features a wonderful video: Aviation pioneers Ruth Nichols and Betty Gillies talk about Long Island's Aviation Country Club in vintage film footage from 1929 with an introduction and historical context provided by Cradle of Aviation Museum curator Joshua Stoff. The country club was a playground for Long Island's elite until 1950, when its land was sold to the developers of Levittown. Credit: Newsday / Chris Ware; University of South Carolina Moving Image Research Collection

Comments

Great story and shout-out!

Found a picture in the Peter Helck Family Collection of the socialite Gillies family of Syosset prior to taking off from Sands Point to participate in the LI Aviation Club’s Eighth Annual Seaplane Cruise.

As obvious as the Gillies are brothers, thinking their wives are sisters to each other; too.

Great lost airfields of Long Island - Nassau County - here,

http://airfields-freeman.com/ny/airfields_ny_longis_nassau.htm

The chronicler of Early Americana/renowned artist Eric Sloane (1905-85) was also heavily involved in aviation, painting murals, writing books for war effort, lettering aircraft for famous flyers of the day at Roosevelt Field. He also painted the enormous mural in the National Air & Space Museum on the National Mall.

Thanks, Howard for the great blog!

Cheers,

John

...and I just found a bunch more Sloane refs on the blog - thank you!

John B.