San Francisco’s 1915 World’s Fair and the Dawn of Championship Auto Racing

Last winter, I assisted author Seana Miracle on an article on the 1915 Vanderbilt Cup Race as part of the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. This is the final product posted on the PPIE100 website.

Enjoy,

Howard Kroplick

San Francisco’s 1915 World’s Fair and the Dawn of Championship Auto Racing

By PPIE100 | March 06, 2015

By Seana Miracle

This year we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the international debut of the Miller Engine, an event that would completely revolutionize the aviation, marine and automotive industries, determine the identity and international relevance of American motor sports, and usher in a Golden Age of championship auto racing.

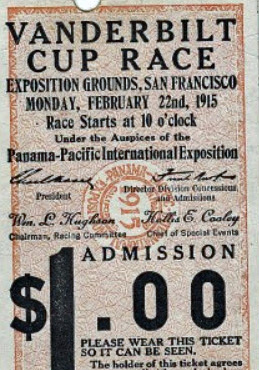

The 1915 American Grand Prix and Vanderbilt Cup Race, held in conjunction with the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, were seminal events in the history of auto racing. They occurred at a critical juncture in motor sports, when the automotive industry was growing at an exponential rate, and right before race car design changed hands from big auto manufacturers to specialized craftsmen. It was the first time that auto racing had been included as part of a World’s Fair, and the first time that the same driver and car won both races in one year.

The car driven to victory, the 1913 Peugeot EX3, was the result of a confluence of recent European and American innovations in high performance engine design. It inspired the first race car engine designed by Harry Miller and Fred Offenhauser. Powerful, lightweight and efficient, the Miller-Offenhauser engines are considered masterpieces of mechanical engineering, and would soon become the most dominant power-plants in American racing history.

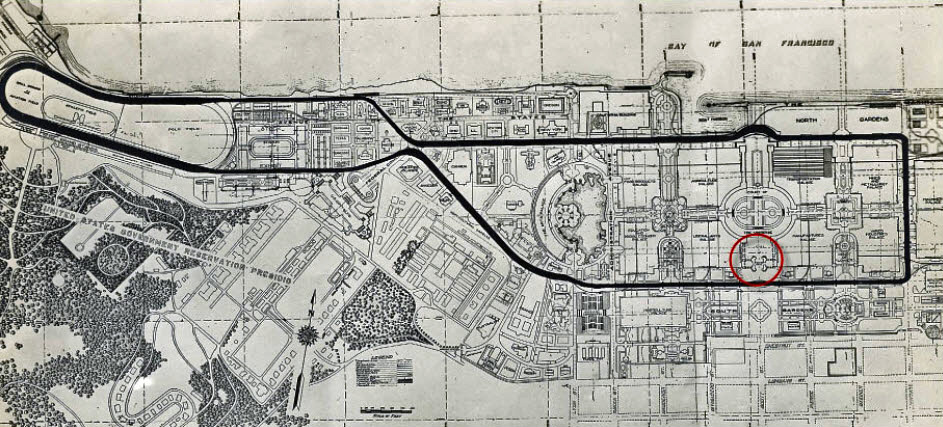

The Grand Prix and Vanderbilt Cup Race are the early precursors to modern day championship racing. Formula One is still known today as “Grand Prix” racing, and the Vanderbilt Cup is the ancestor of what we now know as IndyCar. Both races were held about a week apart, consisted of basically the same starting lineup and used the same course. The American Grand Prix consisted of 104 laps of the course totaling 406.1 miles, while the Vanderbilt Cup Race consisted of 77 laps for a total of 300.7 miles.

The 3.84 mile race course was one of the most scenic and extravagant ever imagined. Combining a road course, a nearby oval, a wooden board main straightaway, and grandstands capable of holding 100,000 spectators, it wound through the Presidio, along the Marina waterfront, and around the Exposition fairgrounds. World-class drivers in state of the art cars whipped past the Tower of Jewels and Great Rainbow Scintillator at speeds averaging well over 60 miles an hour. Never before or since has a race course been so lavishly decorated or beautifully landscaped.

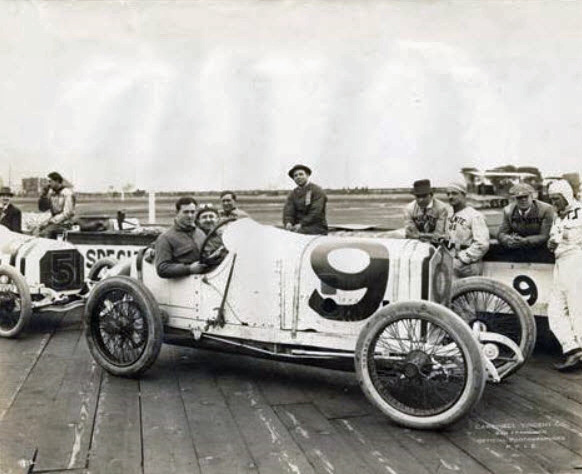

The Grand Prix race, which kicked off soon after Opening Day of the fair, was hit with heavy rains that affected the performance of the vehicles, covered the track in slick mud, obscured drivers’ views, and warped the boards of the straightaway, much to the delight of spectators. This was a highly dangerous time in racing, before any real safety precautions were taken. Enclosed cars and racing helmets would not be developed until over a year later, after a string of tragic deaths. Luckily, no driver or spectator was killed or seriously injured at the Exposition races.

Challenge Cup from Vanderbilt Cup Auto Race held at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Courtesy San Francisco Public Library.

Challenge Cup from Vanderbilt Cup Auto Race held at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Courtesy San Francisco Public Library

Scene from Vanderbilt Cup Race at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Courtesy San Francisco Public Library.

The Vanderbilt Cup was the first major American trophy, and it offered a large silver cup made at Tiffany’s and significant cash prizes that attracted the top drivers and automakers from around the world. Due to the outbreak of war in Europe, the 1915 field was comprised of mostly American talent, but it included some of the most influential icons in the history of the sport.

The competition was formidable. The starting lineup included racing legends such as “Wild” Bob Burnam, the “World’s Speed King,” whose unfortunate death a year later would lead his friends to develop the first enclosed race car. Eddie Rickenbacker, the future owner of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, was one of the country’s top racers, and an aviation pioneer who would go on to become America’s “Ace of Aces” in World War One. Also in attendance was legendary driver Ralph DePalma, winner of the 1912 and 1914 Vanderbilt Cup Race, who would go on to win the 1915 Indianapolis 500, and amass over 2,000 wins in his lifelong career.

The winner of both the Grand Prix and the Vanderbilt Cup Race in 1915 was Dario Resta, an Italian-born British driver for French automaker Peugeot. Resta had been brought to the United States by an American importer of Peugeots to drive the new EX3 after racing legend Eddie Rickenbacker had left the team due to a poor season in 1914. “Baron” Rickenbacker would later consider this the worst decision of his racing career.

Rickenbacker’s replacement, Dario Resta, kicked off his first racing season in America by winning two of the most important races of the season in a little over a week. The car that Resta drove to victory was a Peugeot EX3, featuring a dual overhead cam, four cylinder engine. It’s many innovations included a single iron block and engine head with gear driven camshafts, 4-valves per cylinder, intake valves larger than exhaust, and camshaft intake/exhaust valve overlap, and a new wheel design which allowed for tires to be changed quickly at pit stops.

Driver Dario Resta and the new innovations in engine and body design proved to be a winning combination for Peugeot. Resta went on to win the inaugural 500 mile race at the Chicago Speedway in June of 1915, and almost won the Indianapolis 500 that year, but blew a tire late in the race and was passed by Ralph DePalma for the win. In 1916, in the new EX5, Dario Resta repeated his win of the Vanderbilt Cup, won the Indianapolis 500, and the AAA National Driving Championship. He also took first at the Chicago 300, the Minneapolis 150 and the Omaha 150.

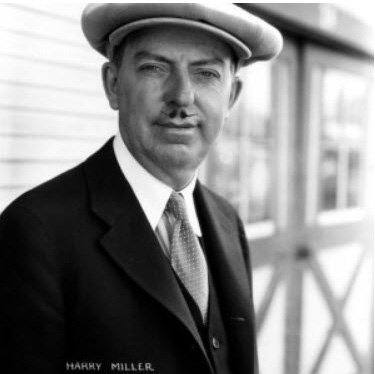

Dario Resta’s sweeping wins in 1915 and 1916 were aided by the innovations of legendary California mechanic Harry Miller, who is considered “the greatest creative figure in the history of the racing car.” Miller’s ingenious high performance engine designs completely revolutionized the automotive, marine and aircraft industries. Since their creation in 1915, almost all class and track records on land or water were held by Miller engines. Miller was also the originator of the race car as an object of art, devoting as much time and labor to aesthetics as he did to technical and mechanical considerations

The first Miller Engine was originally commissioned in 1915 by San Francisco aviation pioneers the Christofferson Brothers. It was an inline six, single-overhead cam aircraft engine, designed in the same manner as Mercedes aero engines of the time, combined with Miller’s recent innovations and meticulous attention to detail. With it’s lightweight, aerodynamic design and impressive power output, it was a stunning achievement. unfortunately, aviator Silas Christofferson died in a plane accident, effectively bringing Miller’s aircraft project to an end.

In 1913, French automaker Peugeot had won the Indianapolis 500 with the innovative L76, the first dual-overhead cam, four cylinder engine in the world. The Indy 500 win was the first time a European car had won at Indy, and it established Peugeot as the team to beat. Competitors complained their cars won practically all the races in which they were entered.

Peugeot’s secret weapon was Swiss mechanical engineer Ernest Henry. Henry’s engines were the first ever to combine dual-overhead cams and four valves per cylinder. Dual overhead camshafts can generally produce more power than single overhead cams, and a multi-valve engine is able to operate at higher revolutions per minute than single valve engines. Today, this technique is the industry standard for high performance engines from powerful Formula One cars to standard production automobiles.

Harry Miller was brought into the racing engine and car construction business by “Wild” Bob Burnam, who hired Miller to rebuild a Peugeot EX3 engine that had blown up at the Point Loma Road Race on January 9, 1915. Bob turned to Miller to design a new replacement engine, and pretty much everything else except for the frame, since the car had been all but destroyed in the accident. Miller combined the mechanical architecture of his predecessor Ernest Henry, with his own uniquely patented aluminum alloys and recent innovations in aerodynamics, to create the first Miller race car engine. “Wild” Bob immediately started winning with the car, which was reported to weigh 200 lbs less and produce 10 percent more horsepower than the original EX3. Before Bob’s fatal crash at Corona in April 1916, he’d ordered another, even more advanced engine from Miller, which introduced another automotive design first: the fully enclosed dual-overhead cam valve train.

Auto racing pretty much came to a screeching halt when America joined the Allied Forces in 1917, and automakers turned to manufacturing arms and military vehicles. After the war, in a booming economy, it would make a spectacular comeback. In the 1920’s, cars were more popular and affordable than ever, making racing accessible to the common man. Under Prohibition, bootleggers had to develop the mechanical know how to modify their cars in order to outrun police, necessitating they also acquire the driving skills to handle high speeds and negotiate winding back roads, which is the origin of today’s NASCAR.

Master engine builders Harry Miller and Fred Offenhauser would command the helm of high performance engine design for the better part of the 20th century. Miller and Offenhauser were already famous for creating efficient engines with astonishing power outputs, but they soon became the masters of supercharging, and developed the first front wheel drive race car. After 1921, Miller race cars would win every annual national championship to follow. Miller was such a formidable presence at Indy 500 that an estimated 83% of the starting field were Millers, and he never placed less than six cars in the top ten. Miller’s successor, Fred Offenhauser would further develop the Miller Engine into the Offenhauser engine. The “Offy,” like the Miller Engine, would dominate racing for decades to come, winning at Indy no less than 24 times in 27 years. Owning a Miller-Offenhauser was considered the standard price of admission if you wanted to compete at Indianapolis.

To this day, ironically, no American team has ever won the American Grand Prix, but Dario Resta can rightfully be considered one of America’s top drivers. Shortly after the races, driver Dario Resta fell in love and married Mary Wishart, the sister of famous race car driver Spencer Wishart. The Restas decided to settle down in Bakersfield, California, and started a small racetrack that is still in operation today. Buttonwillow Raceway Park is one of the most popular and versatile road-course tracks in the country, and the headquarters of the regional SCCA.

Dario Resta’s historic wins of the Grand Prix and Vanderbilt Cup Race in 1915, were in perfect keeping with the spirit of the Panama Pacific International Exposition, which celebrated the collective intelligence of European and American ingenuity, and promised to usher in a Golden Age of prosperity. Thanks to the early influence of racing legends like driver Dario Resta and mechanical genius Harry Miller, today California is one of the premiere international destinations for motor sports, featuring world class tracks like Laguna Seca and Sonoma Raceway, that regularly host Formula One, IndyCar, and NASCAR events.

Special Thanks to racing historians Howard Kroplick, the founder of the Vanderbilt Cup Race website, and Harold Peters, founder of the The Miller-Offenhauser Historical Society, for their invaluable research and exhaustive historical fact checking. This article would not be possible without their many years of hard work and dedication to the subject.

The author, Seana Miracle, is a local historian and former race car driver and race promoter, who helped to open the first road course track in New Mexico.

Comments

Thanks for Keeping American Automotive Racing History Alive!