Williston Times/Roslyn Times “North Shore’s role in road races revisited ”

Richard Tedesco reported on last Sunday's presentation "Then & Now in the Willistons" which was published in both the Williston Times and Roslyn Times.

Enjoy,

Howard Kroplick

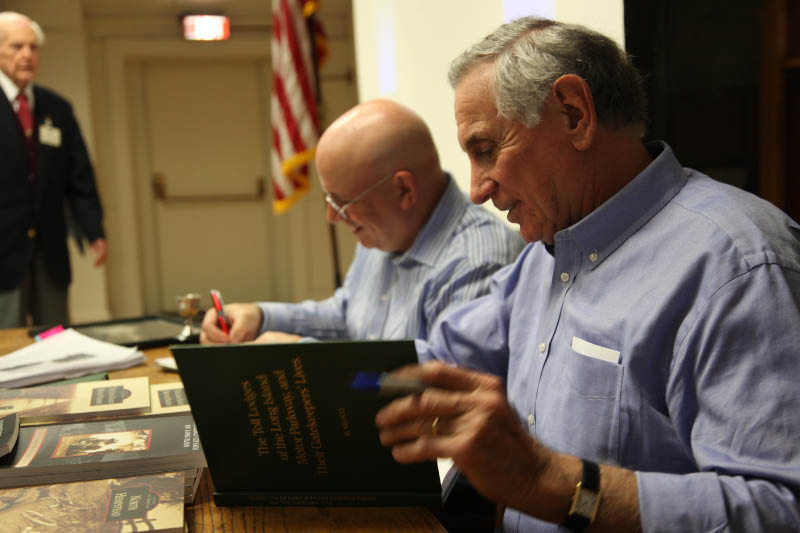

Photo Caption: Town of North Hempstead historian Howard Kroplick (at left) and Al Velocci at Sunday’s lecture in Williston Park on the Vanderbilt Cup Races. Kroplick holds a miniature cup hood ornament sold as a memento by Locomobile when its car won the 1908 race.

The Island Now- Thursday, February 13, 2014

BY RICHARD TEDESCO

At the turn of the century, one of the nation’s biggest annual sporting events was a Long Island road race, and the Willistons were at the center of the action.

“This was like the Super Bowl of its day,” Town of North Hempstead historian Howard Kroplick said of the Vanderbilt Cup Race.

In a presentation at a crowded Williston Park Village Hall last Sunday afternoon, Kroplick and Al Velocci said part of the race followed a route through Williston Park, portions of which still exist including the street named Motor Parkway that runs east behind the American Legion Hall and a segment on the Wheatley Hills Golf Club course.

Kroplick said the race, which was held on the North Shore from 1904 through 1910, drew an international roster of competitors and attracted 25,000 spectators for the first race, and 100,000 for second - at a time when 50,000 lived in North Hempstead.

Kroplick chronicles the race and the parkway in two book he has co-authored with Velocci - “Vanderbilt Cup Races of Long Island” and the “The Long Island Motor Parkway.”

The two authors amassed a collection of 20,000 photographs for the books, which was published by Arcadia Publishing.

The talk, “Then and Now in the Willistons: The Historic Long Island Motor Parkway and Vanderbilt Cup Races,” was co-sponsored by the historic committees of East Williston and Williston Park.

Kroplick said the race and the parkway were conceived by William K. Vanderbilt Jr., great grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt, who was an auto racing enthusiast eager to distinguish himself from the other Vanderbilts.

At Sunday’s presentation, Kroplick screened a two-minute film by American Biograph of the 1904 race, one of the first films of any sporting event, which showed curious spectators crowding onto the course as cars passed them.

While the cars of the day achieved a top speed of 70 miles per hour or more, Kroplick said endurance trumped speed among the racers who drove public roads through 10 laps of the first 30-mile course in 1904.

Each driver, he said, carried a mechanic in the car with him to make repairs, change tires and navigate.

“It wasn’t the fastest car that won. It was the one that lasted,” Kroplick said.

The first course moved west along Hempstead Turnpike into Floral Park and then east along Jericho Turnpike over public roads, sparking objections from some residents

“Of course there were protests. Farmers objected to closing the roads on a Saturday,” said Kroplick. Local volunteer fire departments and post offices also opposed the races, he said.

“Chain your dogs and lock up your fowls,” posters of the day warned before the 1904 race.

That did not stop the race’s organizers from adding I. U. Willets Road and Willis Avenue to the 1906 race.

Big names in the automotive world participated in the Vanderbilt Cup that year, including Louis Chevrolet and Vincenzo Lancia, who went on found and design Lancia cars. Lancia finished second in the 1905 race.

But when a spectator was killed in the 1906 race, Kroplick said, “It looked like it was going to be the end of racing on Long Island.”

Kroplick said the American Automobile Association, which sponsored the race, discouraged racing on public roads and for two years the race was not held.

But Velocci said, “Some wiser heads prevailed.”

Vanderbilt and his racing commission announced plans to build a race course so public roads would not be used.

Construction on what would become the Long Island Motor Parkway started in 1908, as a new era for the Vanderbilt Cup Races, and roadway design, began.

The Long Island Motor Parkway ran approximately 10 miles from Merrick Avenue in Westbury to what is now Bethpage. The expanded parkway went through the Willistons, becoming a toll road in 1909.

Velocci said the motor parkway featured a slight crown to facilitate drainage featured room for three cars, and banked sections of road.

Nine miles of the parkway were used in the 1908 race course, and as the outcry against use of public roads subsided, the 1908 also included 15 miles of public roads, Kroplick said.

Kroplick said interest in the race peaked in 1910 when 300,000 spectators attended. But he said one car went off a parkway bridge and Chevrolet’s mechanic was killed when his car also crashed.

That ended the race series on Long Island, although it continued in other cities through 1916.

Meanwhile, the motor parkway became a toll road that remained in use until 1938.

“It’s the first road built exclusively for automobiles,” Kroplick said. “It helped transform Long Island from farmland to a sprawling suburbia.”

He said the use of reinforced concrete, guardrails, landscaping and bridges to eliminate intersections were all innovations at the time.

Kroplick and Velocci are both members of the Long Island Parkway Preservation Society.

Velocci said his interest in the parkway was sparked when he lived in New Hyde Park for several years. Kroplick’s interest grew out of a trip to the Vanderbilt Museum.

Kroplick, a resident of Roslyn, now owns a piece of Vanderbilt Cup history: the 1909 Alco-6 Racer dubbed Bete Noir (Black Beast) that won the two Vanderbilt Cup Races in 1909 and 1910.

His “then and now” presentation on Sunday included photographs of vintage vistas of the Willistons, including the Krugs East Williston Hotel formerly at the intersection of Jericho Turnpike and Willis Avenue, a shot of the Hotel Monticello where Weigands Funeral Home now stands, the Williston National Bank, in the parking lot of today’s Bank of America and the corner of Hillside Avenue and Broad Street, where the buildings are essentially unchanged - along with one other constant feature.

“The one thing that never changes over 100 years is the telephone poles,” he said.

Comments